Data is just that – data. It can tell stories, but those stories can be understood in wildly different ways even when supported by the same data. Which is why story matters. It matters to your business, your career, and your life.

I’ll walk through an example I have used in a critical thinking class I taught in fall.

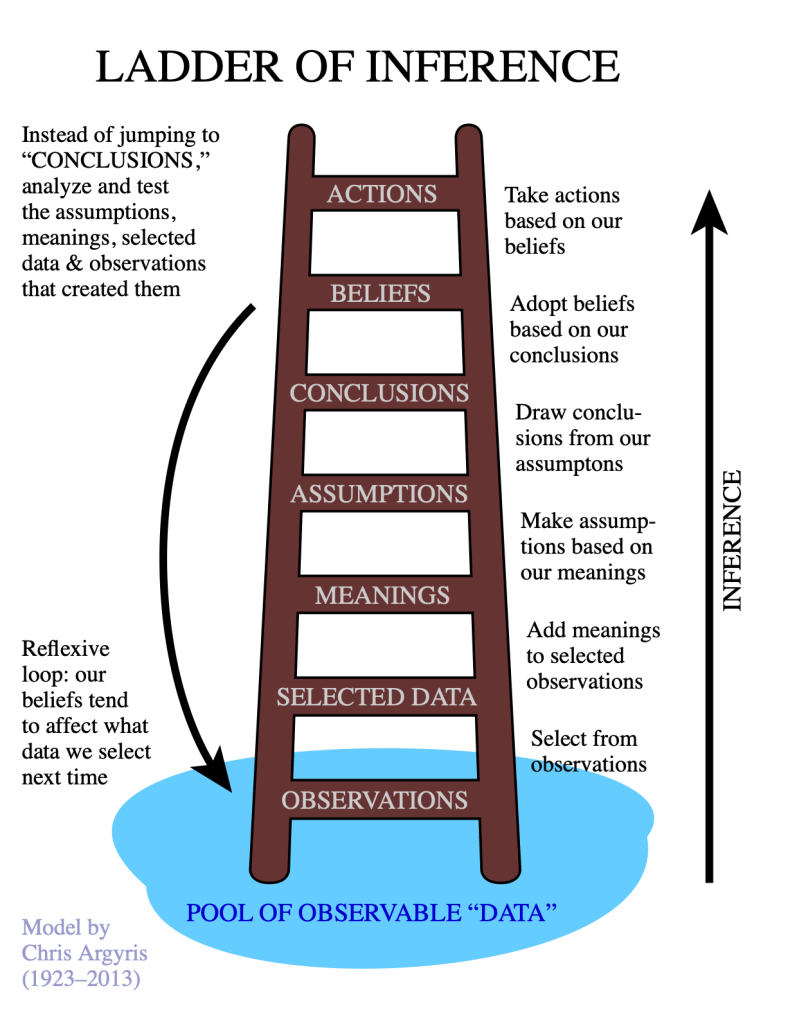

There’s something called the Ladder of Inference that helps to explain how our minds create micro-stories all the time. The beauty of the Ladder is that it highlights how the models we use to think about the data we encounter can change our beliefs and actions.

The Ladder consists of several rungs

- We have observations aka data

- We select some of that data to attend to

- We assign meaning to that data

- We make assumptions about what the data means

- We draw conclusions

- Those conclusions create beliefs

- We take action based on those beliefs

With so many steps between observed (or measured) data and action, there are plenty of places for alternatives to enter, particularly as we make meaning and assumptions and draw conclusions. This is why if we want people to understand the data, we have to help them navigate the ladder, otherwise they might come up with a different belief and action.

Take this simple scenario for example,

You arrive at a party. You spot a friend across the room. You wave. They turn around.

The Ladder of Inference based on this data might look like this:

- You arrive at a party. You spot a friend across the room. You wave. They turn around.

- You select to attend to the friend and their turn around.

- You think they turned because they didn’t want to look in your direction.

- You assume that is because they don’t wish to speak with you.

- You conclude they must be angry with you.

- You believe you are not welcome.

- You leave the party

The Ladder of Inference based on this data might also look like this:

- You arrive at a party. You spot a friend across the room. You wave. They turn around.

- You select to attend to the friend and their turn around.

- You think they turned because they didn’t need to look in your direction.

- You assume that is because they were watching to see when you arrived.

- You conclude they may have been worried and are now reassured you arrived safely.

- You believe they care about you.

- You make your way across the room to say hello, feeling happy that your friend cares.

Quite the difference, no?

In our scenario, there is no evidence that the friend is angry. There is also no evidence that the friend is worried. We are only attending to two data points: the wave and the turn around. There’s likely more data in this scenario that we aren’t attending to. But those data points produce an interpretation, an inference, that then colours the rest of this small interaction.

Most of the time we operate on partial data in life and work. And when we are presented with facts, we do our best with the data we have to interpret them.

But that’s risky if your customers, clients, investors, or even your family and friends only have some of the data. They may craft a story that is very different than your story.

And the last step in the ladder: take action, varies depending on the story that gets constructed. If you want people to take the action you intend based on the data you present, you need to walk them through the story to get to that action.

So it’s important to make sure you are telling the story that guides your listener to the action you want.

Leave a comment